Universal rights and Imperialism’s neo-liberalism offensive

225/11/2017 by socialistfight

By Ret Maruat, Socialist Fight Issue No. 2 Summer 2009

Imperialism’s neo-liberalism offensive since the 1980s cloaked its brutal advance against the working class and poor of the world by a hypocritical championing of ‘democracy’ and ‘rights’ – from ‘democracy’ within trade unions and ‘democracy’ for the USSR and Iraq all based on the ‘free market’ and ‘free trade’. This ideological offensive left its victims far poorer and with far less effective collective rights. ‘Revolutionaries’, like the SWP, hailed the fall of the Berlin Wall, the neo-liberal counterrevolution’s greatest achievement. They thereby foolishly welcomed their own political marginalisation. Ret Marut examines the ideological roots of this offensive and outlines Marxism’s answers.

Fighters for Rights: Eleanor Roosevelt (1948 UDHR) and Rosa Parks (1955 Black civil rights)—the black ghettos of the US are worse now than back then.

Fighters for Rights: Eleanor Roosevelt (1948 UDHR) and Rosa Parks (1955 Black civil rights)—the black ghettos of the US are worse now than back then.

We will firstly look at the international order to see how human rights fare under four models of the system; realism, liberalism, constructivism and Marxism. We will use the book on global political economy Ordering the International, History, Change and Transformation, eds, Brown, Bromley, and Athreye Pluto Press, OU, London, 2004 as our main source.

Now to see how these models might lead to transformation by regimes of universal human rights and justice we will look primarily at the two models that propose a transformation perspective; liberalism and Marxism. Now in transformation we will need to examine the power structures of modern society.

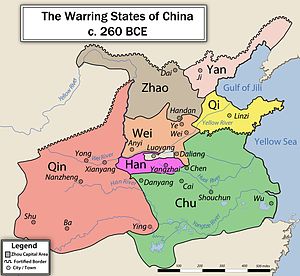

To do so we must examine where we are coming from and going to; we must look at the history of state systems; the Chinese warring states (c.770 to 221 BCE) and the nineteenth century evolution of modern Europe and then the modern world. Lastly we will look at international theories of globalisation to see how socio-cultural issues impact, what is the potential of information and communication technology (ICT) and how and in what way the current sub-prime financial crisis or the overwhelming superiority of the US military has the power to transform the international order.

Realism, liberalism, constructivism, and Marxism

Kenneth Waltz propounds the modern version of realism as historically developed by Thomas Hobbes and advocated and practiced in recent times by Hans Morgenthau and Henry Kissinger. Although the former opposed the Vietnam War the latter organised the illegal bombing of Cambodia (1969-73) and the 1973 coup in Chile against Allende, both advocating the best interests of the US. Realism puts a strong emphasis on national security and interests and assumes international anarchy in inter-state relationships with no relationship between domestic and international politics.

The modern liberal theory of the international state systems’ goes back to Immanuel Kant. Its core premises are as defined by Moravcsik. That is (if we can read between the lines) it is the interests of competing national capitalists which are fought out both nationally and internationally and the struggle is to find the best methods of extracting the maximum profits with as little conflict as possible. So ‘Moravcsik (1997) sees a world of individual and group interest organised within, and represented through, the institutions and agency of the state’ (Ordering, p496). It follows that all states in the modern world seek to represent the interests of that state’s ruling elite.

Constructivism is ideas-based. That is it is philosophically idealist in that it sees the prevailing cultural norms as determining the relations between states rather than the material social and power relations between states determining or at least substantially modifying international cultural relations. Constructivism, despite its more ‘social’ orientation, is as bad as realism on the potential of rights and democracy, let alone genuine human liberation, and so leaves us with nowhere to go on transforming international relations.

Marxism views the world as it moves and changes and sees the things that comprise modern society, commodities, private property, states, legal structures, etc. as embodying relationships between people. It is a theory that takes the social relations of production, the relationships we must enter in order to make a living, as historically evolved and evolving. Moreover, these relationships are at a different level and/or have their own historically-evolved peculiarities in all countries. However this unevenness of development is complemented by a combined character; certain limited sectors of underdeveloped states have become highly developed and out of sync with the rest of their overwhelmingly backward, rural societies.

How the international system might be transformed under liberalism

The liberal version of the world order was articulated by Bill Clinton to the UN General Assembly in 1993, ‘For our dream is a day when the opinions and energies of every person in the world will be given full expression in a world of thriving democracies that cooperate with each other and live in peace’ (Ordering, p107). This ‘dream’ dominates the world, even when the realist Republicans are in power. The liberals spell out their dream; ‘any given state must be ‘a local guardian of the world republic of commerce’. Moreover, liberal states should develop international intuitions and forms of international law to ease commercial transactions across their borders, thereby advancing the benefits of the division of labour and specialisation and political cooperation on an international scale’ (the quote from Hirst, 2001, p64, as quoted in Ordering p110).

Here the Kantian dilemma appears; even if we concede to Hobbes that security can be permanently solved within states how can we solve it internationally? All of Kant’s theories relied ultimately on moral imperatives because international security can only be solved in liberal terms by overcoming anarchy by a world state with its own legal system, police, and armed forces.

This is a utopian goal that not even Clinton would advocate because we know that the self-assumed role of the US as the world’s policeman is not acceptable to its closest allies, Britain, Australia or Canada, let alone to the Middle East, Latin America, Africa or Asia. However Kant did recognise the limits of liberalism and conceded that it ‘remained, in the end, a set of regulative ideals and empirical tendencies, not a utopia beyond all political differences’ (Ordering, p563).

Note the encirclement of the Gulf and the Caspian Sea

Note the encirclement of the Gulf and the Caspian Sea

Let us see how Kant’s dilemma works out in practice. Military intervention to ensure the global spread of these liberal values became the policy of the US after 1991. Yugoslavia began to break up under economic and ideological pressure mainly from Germany and the US. All warring sides engaged in ethnic cleansing but the Serbs were the only ones demonised in the western media. But it was the intervention in Kosovo by the US military that exposed the real thrust and hypocrisy of the rights propaganda. In June 1999, just after NATO had bombed Yugoslavia, the US began the construction of Camp Bondsteel. According to the World Socialist Web Site,

In April 1999, British General Michael Jackson, explained to the Italian paper Sole 24 Ore:

“Today, it is absolutely necessary to guarantee the stability of Macedonia and its entry into NATO. But we will certainly remain here a long time so that we can also guarantee the security of the energy corridors which traverse this country.” The newspaper added, “It is clear that Jackson is referring to the 8th corridor, the East-West axis which ought to be combined to the pipeline bringing energy resources from Central Asia to terminals in the Black Sea and in the Adriatic, connecting Europe with Central Asia”.

Simon Bromley, in his Blood for Oil, also sees this as fundamental to recent US military interventions:

The routing of pipelines, the policing of shipping lanes and the management of regional influences all depend heavily on US geopolitical and military commitments. This means, in turn, that to the extent that US companies and US geopolitics – and especially military power – remain central to ordering the world oil industry, the USA provides, in good times, a collective service to other states that enhances its overall international hegemony. In bad times, this role would provide the USA with a potential stranglehold over the economies of potential rivals.

It is clear from this that the human rights of the Kosovan Albanians were only a cover for the real drive of US imperialism. In a New Political Economy article in 2004 Robert Cox points out that European powers were clearly miffed by this unilateralism of the US. Roma, Croatian and Muslims in the region were ethnically cleansed by the US sponsored neo-fascistic Kosovan Liberation Army.

Kant’s dilemma is further emphasised by the operation of the International Criminal Court (ICC). Serbian President Slobodan Milošević and Sudanese President Omer Hassan Al-Bashir were indicted by the prosecutor of the ICC whilst they were reigning heads of state. There was no question of indicting US ally, President of Croatia Franjo Tudjman, or other allies whose human rights record would not stand scrutiny. Pinochet was never tried despite all the universal justice brouhaha.

And the US itself refuses to recognise international law. In 1986 President Regan contemptuously rejected the guilty verdict against the US by the ICC for supporting the Nicaraguan Contra rebels. Of course in the Balkans and Iraq the US aimed not only to secure control of oil but also, and we would say primarily, to eliminate regimes which opposed the neo-liberal free market economy that so favours the economically powerful.

How the international system might be transformed by Marxism

Marx made the first socialist criticism of the bourgeois secular regime of rights in 1843 in On the Jewish Question, the ideological foundation for his later critique of capitalism as a whole. The basic argument is that the secular regime of rights as developed by the American and French Revolutions at the end of eighteenth century represented civil but not human emancipation. He examines The Rights of Man and Citizen (1789) and passages from others constitutions to make his point. It equally applies to the UN Declaration of Human Rights of 1948. As Marx shows in On the Jewish Question these rights presuppose increasing inequality because they bifurcate human lives and psyches, the citizen equal before the law and in voting rights and as he really exists in society, alienated, oppressed and exploited,

Where the political state has attained its true development, man – not only in thought, in consciousness, but in reality, in life – leads a twofold life, a heavenly and an earthly life: life in the political community, in which he considers himself a communal being, and life in civil society, in which he acts as a private individual, regards other men as a means, degrades himself into a means, and becomes the plaything of alien powers… the right of man to liberty is based not on the association of man with man, but on the separation of man from man. It is the right of this separation, the right of the restricted individual, withdrawn into himself (Marx, On the Jewish Question).

But of course the new regimes of rights were a big step forward compared to the arbitrary, absolutist power of monarchs, nobility and church in the Ancien Régime. In examining the conflicting claims of cosmopolitans vs. communitarians, cultural relativism, feminist arguments and Asian values we will keep Marx’s vital distinction in mind.

Jef Huysmans is correct to point out that it is false to project a clash of civilisations as Samuel Huntington and Osama Bin Laden do because societies are in internal conflict (Chapter 9 of Ordering). The ‘cultural values’ of the communitarians do implicitly defend reactionary practices like wife beating and female circumcision which are fiercely opposed by female activists increasingly informed by radio, satellite television, mobile phones, etc. But we can see that the communitarians’ arguments echo Marx in counterposing the alienation of cosmopolitan, oppressed civil man as against ‘life in the political community, in which he considers himself a communal being’. Without conceding to localism in this their criticisms of cosmopolitanism is trenchant and rings true.

Rights were guaranteed by the state and applied to its citizens before 1948 although there was some attempt to universalise rights, e.g. the Geneva Convention, etc. The ideological content of the Declaration was the struggle of the US to end all opposition to the global free market: fascism, the old colonial empires, communism (‘really existing socialism’) or world revolution (not the same thing). There were seven votes against the 1948 Declaration; South Africa and Saudi Arabia, for obvious repressive reasons, and the USSR and four satellites for two contradictory reasons. One was repressive but the other was progressive; they objected to the Declaration because it contained no reference to collective rights like food, water, housing, healthcare, etc. The Soviet societies claimed their legitimacy because they partially compensated for their repression by providing a measure of these welfare needs. Social justice versus greedy capitalist individualism was their propaganda stance. In the Cold War, the ‘non-aligned’ movement tended to be dictatorial like Syria, Iraq or Nasser’s Egypt which talked a lot about Arab socialism and provide some welfare. The USSR provided a rationale for patronising welfare and repression which had independent economic developmental prospects; it was grudgingly tolerated by the poor because it was better than outright repression with no welfare by such the US supported and/or installed regimes as Mobuto’s Zaire or Pinochet’s Chile.

We are focused on this issue by the question of how we would feel if, on transportation into future, we discovered we had a brand new right – we had an absolute right to keep all our fingers and toes and no one could take them from us. Such a right would make us very uneasy and this highlights the essence of the rights argument, we only need rights if our possessions or security are threatened (Tutor’s handout). And here the rights debate is situated. What value is the right to vote and protest in conditions of famine? Of course the poor, hungry and starving would accept a great diminution of legalistic ‘human rights’ if they were guaranteed decent welfare provisions.

These arguments had some force while the USSR existed; the neo-liberal offensive, led by the US and Britain, was additionally kept at bay by working class resistance and defence of the welfare states in the advanced metropolitan countries. When the British miners were defeated in 1985 and the USSR fell in 1991 history was supposedly ‘ended’ (Fukyyama) by these dual and closely related defeats suffered by the world working class in terms of the triumph of the free market over social justice.

Transformation by technological development; globalisation theory

Benno Teschke cogently argues that the modern state system originated not in the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia but in late seventeenth century post-revolutionary England. The King-in-Parliament signified the economic (although not yet fully political) domination of capitalist property relations which went on to dominate world trade and commerce. Although he barely mentions the great significance of the English-opposed French Revolution in ideologically universalising this system nevertheless he clearly demonstrates that the extraction of the surplus by the inescapable but ‘democratic’ wages system rather than by the forcible extraction by the law and taxes of feudalism and absolutism is the mode of production dominant on the planet today (Ordering, Chapter 2).

The brief reference to the Chinese warring states (c.770 to 221 BCE, Ordering, p6-7) explains that philosopher Mozi wanted a balance of power to protect the small and weak states but Mencius wanted a unified Chinese world state, in an ancient version of the cosmopolitan-communitarian debate. These political differences and local power aspirations were overcome by reunification under the rule of the Qin Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi in 221 BCE. If we look at The Warring States Period in Answers.com we realise that the resolution was prepared by developments in trade and commerce which challenged localism and by technology as bronze gave way to iron facilitating the transformation of war from aristocratic chariots jousts to mass armies, thereby favouring the larger states. Ideological conflicts between the followers of Mozi and Mencius depended on this material basis.

Similarly, the superior productive basis of the capitalist British economy prevailed in the eighteenth up to the last quarter of the nineteenth centuries, in the first globalised world economy. Adam Smith gave an ideological expression to the orientation necessary to maximise this material advantage. And it was Taylorism; scientific management and Fordism; mass production that made the US the world’s most advanced and efficient economy and converted the political opinion of the US elite to the goal of global hegemony even before WWII. The above case as presented in Ordering might be seen as realist or constructivist. The details supplied by Answers.com make it a Marxist analysis of transformation but it might equally be a liberal one

Whereas theories of globalisation explain the modern developments by technology innovation and the expansion of world trade ‘globalisation theory’ as advocated by Manual Castells and Marshall McLuhan is a constructivist, idealist notion that inverts the reciprocal relationship between cause and effect; it turns effect into cause. Information can only increase the efficiency of global production (‘just-in-time production’ etc.), but it is not a ‘new capitalism’ replacing industry; it is merely a tool of production. The current sub-prime financial crises have demonstrated that information shuffled about on global networks by ‘fund managers’ glorified vastly overpaid parasitic bank clerks do not create wealth, merely swindle wealth producers out of the product of their labour.

Although the communication advantage in the international production of wealth enhances the profits of transnational corporations it certainly does not represent ‘an unburdening of state power and its redistribution across mobile, ever-shifting networks’ (Ordering, p565). Who but states can even address the current financial crisis? And who can doubt that this crisis is materially transforming the US position as world hegemon? No empire survives economic meltdown, this was the cause of the British and Russian falls, and with a gross external debt of over $13 trillion as of June 2008 even before the current crisis (Wikipedia), it is clear that the process of US decline has been enormously speeded up.

As Audio 9 points out the vastly superior technological war machine of the US combined with ICT enabled it to overcome the fog of war and devastate Iraq’s inferior armed forces. But the same ICT enabled isolated cells of oppositionists to network against the occupying army (al-Qaeda) and so gave them the advantage. The global eco-warriors and ‘make poverty history’ networks that massed at Seattle and Genoa were only ever a ‘soft power’ movement now largely spent because they cannot match the ‘hard power’ of George Bush’s war machine or the international capacity of organised labour to force concessions from the bosses by the withdrawal of labour. These networks of dissent targeted the WTO and the IMF and not the nation states where lies real economic and political power. These movements highlighted the necessity for dissent to mobilise internationally but they also highlighted the failure of the only ‘hard’ alternative to globalised capital, the international labour movement to do so.

Culture and human rights

But there are, nonetheless, real issues of human right violations that the propaganda of rights highlights and cause to develop. In Iran today the Islamic regime of Ahmadinejad denounces women’s rights activists and trade unionists as stooges of western imperialism and demands national unity in the face of threatened US/Israeli attack. Mansour Osanlou, leader of the Teheran Vahed Bus Company union and many other are in prison because they attempted to organise trade unions. Is it not Islamic culture to wear the hejab, to marry the husband chosen by your father or brother, and reject western intuitions like trade unions? Does not the Shi’i, as opposed to the Sunni, champion the mustazifin, the oppressed, against the mustakbirin, the oppressor? Iran has a developed civil society with a large and prosperous middle class so while women have to endure many humiliations at the hands of the religious police and Revolutionary Guards they have managed to maintain many rights and privileges not available to their Islamic sisters and brothers in Pakistan’s and Saudi Arabia’s less developed societies.

Although united by the Quran, dedication to the Prophet, religious rites and shari’a law the culture of Islam differs greatly betwee societies and between Shi’a and Sunni. Islam has three main political orientations; the conservative or salafi Islam dominant in Saudi Arabia (Wahhabi Islam) with strong support through the Islamic world. It is repressive and hostile to women’s rights and intellectual freedom. The second is a radical and militant version of the first which puts its emphases on direct action as opposed to state oppression and is associated with Sayid Qutb of the Egyptian Muslin Brotherhood (MB), executed in 1996. The third is reformist and tends to marry Islam to a secular attitude to rights and freedoms. It is found mainly in Turkey and Egypt and in thereformist Islamists of Iran (although differing between Shi’s and Sunni).

The Muslim Brotherhood (MB) in Egypt were originally a brand of militant Islam which sought to impose a literal interpretation of shari’a law, advocated jihad against all liberal intellectuals and non-Muslims and found co thinkers in Algeria, Iran and Afghanistan (the Taliban) and al-Qaedia. Since they were founded in 1928 they had been repeatedly repressed by the Egyptian state because of alleged assignation plots. However the Egyptian state today is developing a modus vivendi with the MB which is still illegal although tolerated. It has wide electoral support, has demonstrated in favour of democracy and probably would win a democratic election and rule in a similar way to Turkey’s AKP government. It was a more militant organisation with support in North Africa, Jihad Talaat al-Fath, which carried out the Luxor massacre in 1997.

This accommodation comes at the same time as the rise of the Egyptian trade unions which are now severely oppressed by the Egyptian state. This is arguably a fourth and vitally important political current within the Islamic world. Modern Egypt is beginning to tend towards the reformism of Muhammad Abduh (died in 1905) who reinterpreted Islam to grant full citizenship to Christians and Jews. Arguably the MB is transforming itself into the third, reformist, type along these lines. The advance of the MB and the AKP are examples of the accommodation of Islam to modern capitalism, not the advance of fundamentalism. We are far from a simplistic Huntington-type ‘clash of civilisations’ in the Islamic world but rather are seeing transformations led by economic developments and political conflicts.

In the US the experience of the wartime comradeship of military service reinforced by the UN Declaration was a major contributing factor to the rise of the Black civil rights movement which later led to the women’s and gay and lesbian civil rights movements in the US and then worldwide. If we look at the outcome of these civil rights movements they are all disappointing in terms of human liberation. The first has resulted in career opportunities for a small Black middle class; Barak Obama is the best example of a group which includes Oprah Winfrey, Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice. In 1992 Dr. Richard Majors, a psychologist at the University of Wisconsin at Eau Claire, pointed out,

*About one in four black men aged 20 to 29 is in prison, on probation or on parole – more than the total number of black men in college.

*For black men in Harlem, life expectancy is shorter than that for men in Bangladesh; nationally, black men aged 15 to 29 die at a higher rate than any other age group except those 85 and older.

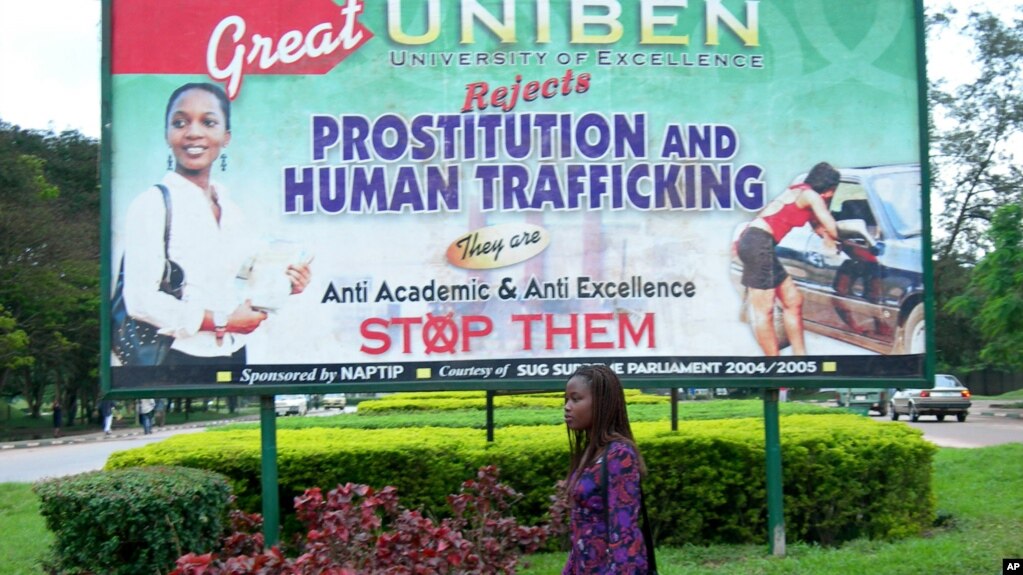

We could make similar points for the outcome of all the other struggles arising from rights; in the north of Ireland inter-communal relations are worse now than during the ‘troubles’, South Africa’s neo-liberal ANC has left the position of the black poor almost as bad as under apartheid, as seen by the recent riots against Zimbabwean immigrants. Women are particularly disadvantaged because ‘such (sexual and reproductive) human rights abuses are not prevented by universalised human rights conventions’ so the argument goes in the face of ‘the powerful and dominant’. The growing trafficking of young women by criminal gangs for prostitution and semi-slavery is another victory for the free market. So fighting for rights might be the beginning of a struggle, this cannot be the basis for victory as the above indicates and as Marx indicated back in 1843. But rights will always be necessary as long as want and oppression exist.

Conclusion

Bill Clinton’s and Barak Obama’s American dream is still by far the most universally appealing one today. However, the modern neo-liberal capitalist offensive is now floundering because of the depression following the spectacular collapse of so many major financial intuitions. Modern capitalism is the source of all cooperation but also of all conflict and rivalries; it proposes a utopian world free from war and conflict but prepares those same wars and conflicts as states promote its relentless drive to maximise the profits of the TNCs. The transformation potential of Marxist theory lies in the acknowledgement of an objectively evolving source of international conflict in Trotsky’s theory of combined and uneven development.

However, the conclusion for human liberation is contested by those who call themselves Marxists. The Stalinist view is that a national elitist and privileged bureaucracy can deliver to the masses via state-controlled planning with little regard for human rights or democracy. The production of superabundance, the material precondition for human liberation, is only possible on a global scale. Stalinist ‘socialism in a single country’ (North Korea!) is even more unthinkable now. The Marxist aspiration is world revolution and one world planned economy producing for human need. That is the difference between a civil regime of rights which presupposes inequality and a human regime of real economic and social equality based on the production of the superabundance of wealth, which Marx outlined in The German Ideology.

A Canadian primary schools celebrates the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which still eluded humanity

A Canadian primary schools celebrates the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which still eluded humanity

Index of names (in order of appearance in text, Wikipedia unless stated)

Kenneth Waltz, (born 1924) is a member of the faculty at Columbia University and one of the most prominent scholars of international relations alive today. He is one of the founders of neo-realism, or structural realism, in international relations theory.

Thomas Hobbes, (April 5, 1588 – December 4, 1679) was an English philosopher, whose famous 1651 book Leviathan established the foundation for most of Western political philosophy from the perspective of social contract theory.

Hans Morgenthau, (February 17, 1904 – July 19, 1980) was a pioneer in the field of international relations theory. He taught and practiced law in Frankfurt before fleeing to the United States in 1937 as the Nazis came to power in Germany.

Immanuel Kant, 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was an 18th-century German philosopher from the Prussian city of Königsberg (now Kaliningrad, Russia). He is regarded as one of the most influential thinkers of modern Europe and of the late Enlightenment.

Andrew Moravcsik is a Professor of Politics and director of the European Union Program at Princeton University known for his research on international organizations, human rights, European integration, and American and European foreign policy, and for developing the theory of liberal intergovernmentalism.

Jef Huysmans, obtained a MA in Defence and Disarmament studies from the University of Hull, UK and a PhD in social sciences from the University of Leuven, Belgium. He is now Lecturer in Politics at Open University (University of Birmingham).

Samuel Huntington, (born April 18, 1927) is an American political scientist who gained prominence through his ‘Clash of Civilizations’(1993, 1996) thesis of a new post-Cold War world order.

Simon Bromley joined the Open University in 1999, after teaching and research at the University of Leeds. He is currently Associate Dean (Curriculum Planning) in the Faculty of Social Sciences and Course Chair of the Faculty’s new level 1 foundation course in the social sciences (Open University).

Francis Fukyyama, The End of History and the Last Man is a 1992 book by Francis Fukuyama, expanding on his 1989 essay ‘The End of History?’ published in the international affairs journal The National Interest. In the book, Fukuyama argues that the advent of Western liberal democracy may signal the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the final form of human government.

Benno Teschke joined the Department in summer 2003 had been a Lecturer in the Department of International Relations & Politics at the University of Wales, Swansea. In 1998/99, he was an Andrew Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow at the Center for Social Theory and Comparative History at the University of California, LA. (University of Sussex).

Mozi, ca. 470 BCE–ca. 391 BCE), was a philosopher who lived in China during the Hundred Schools of Thought period (early Warring States Period). He founded the school of Mohism and argued strongly against Confucianism and Daoism.

Mencius, most accepted dates: 372 – 289 BCE; other possible dates: 385 – 303/302 BCE) was a Chinese philosopher who was arguably the most famous Confucian after Confucius himself.

Qin Shi Huangdi, (259 BC – September 10, 210 BC), was king of the Chinese State of Qin from 247 BCE to 221 BCE. He became the first emperor of a unified China in 221 BCE. He ruled until his death in 210 BCE, calling himself the First Emperor. He was known for the introduction of Legalism and also for unifying China.

Adam Smith (baptised 16 June 1723 – 17 July 1790 was a Scottish moral philosopher and a pioneer of political economy. One of the key figures of the Scottish Enlightenment, Smith is the author of The Theory of Moral Sentiments and An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Adam Smith is widely cited as the father of modern economics.

Manuel Castells, born 1942 in Hellín, Albacete, Spain) is a sociologist associated particularly with research into the information society and communications. According to the Social Sciences Citation Index’s survey of research from 2000 to 2006, Castells was ranked as the fifth most cited social sciences scholar and the foremost cited communications scholar in the world.

Marshall McLuhan, C.C. (July 21, 1911 – December 31, 1980) a Canadian educator, philosopher, and scholar, a professor of English literature, a literary critic, a rhetorician, and a communications theorist. McLuhan’s work is viewed as one of the cornerstones of the study of media theory. McLuhan is known for coining the expressions ‘the medium is the message’ and the ‘global village’.

Sami Zubaida (born 1937) is an Emeritus Professor of Politics and Sociology at Birkbeck, University of London and, as a Visiting Hauser Global Professor of Law in Spring 2006, taught Law and Politics in the Islamic World at New York University School of Law.

[…] [14] Ret Maruat, Socialist Fight Issue No. 2 Summer 2009 Universal rights and Imperialism’s neo-liberalism offensive, https://socialistfight.com/2017/11/25/universal-rights-and-imperialisms-neo-liberalism-offensive/ […]

LikeLike

[…] [5] Extracted from, Ret Maruat, Socialist Fight Issue No. 2 Summer 2009, Universal rights and Imperialism’s neo-liberalism offensive, https://socialistfight.com/2017/11/25/universal-rights-and-imperialisms-neo-liberalism-offensive/ […]

LikeLike